Physics, Fortran, and the Art of Simulating Reality

You can see my Academic CV here.

2011 was my first year in college studying Physics. By the second semester I was having my Programming 101 course and started on a project to simulate some networks. Back in those days, I spent an unreasonable amount of time wrestling with numerical simulations—because apparently, physics isn’t hard enough without adding buggy code to the mix. If there’s one thing physics departments love more than blackboards, it’s Fortran, a language that’s been extinct everywhere except academic basements since the 90s.

(I actually really like it? Its a strong typed language and I would constantly consider what sized integer or float I was going to need. The only thing that I was annoyed by was that we could not create an array without defining its size beforehand)

The One-Dimensional Apocalypse (Or: How I Learned to Love Edge Cases)

My professor dropped this problem: “Imagine a line of 100 million people, each whispering only to their immediate neighbors. Some of them are sick. Every second, each infected person either:

- Infects a neighbor (with probability λ%), or

- Spontaneously recovers (because time cures everything).

Now simulate a million interactions. Is there a specific λ value where the disease start to spread indefinitely?”

At first glance, it felt like modeling a very boring zombie movie—patients zero shuffling left and right, occasionally coughing on neighbors or suddenly deciding they’re fine. But buried in that simplicity was a devilish question: Could tiny local rules create predictable global pandemics?

Spoiler: Yes. The model’s behavior flipped dramatically based on λ:

Small λ: Infections fizzled out like a damp firework

High λ: Everyone got sick, always

λ at a precise spot in the middle: Mathematical chaos. The system became a moody artist—sometimes dying out, sometimes raging forever.

The kicker? This is exactly how forest fires spread, how rumors propagate, and—years later—how my advisor would model early COVID-19 contact tracing. All from a glorified game of telephone.

There and back again

The latter half of my undergrad and through my Masters I avoided coding as much as possible. I would rather spend a couple of hours solving an ODE by hand than write a single line of code to get an approximated result. But as a fate of destiny would have it, I ended up doing a PhD in Theoretical Physics and my advisor really wanted someone to code.

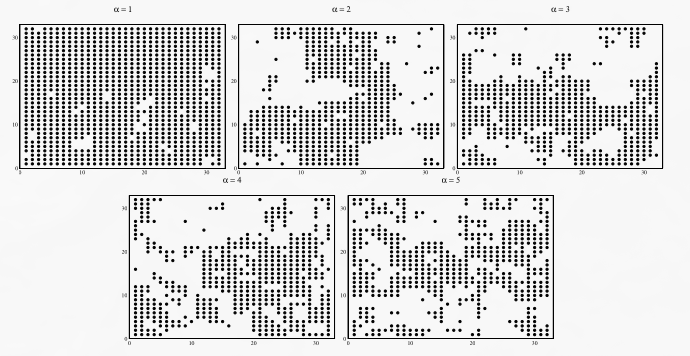

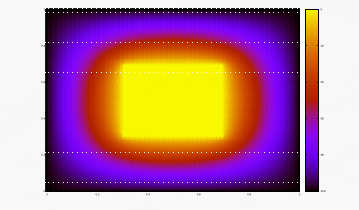

So I had this class where I was the only student and the professor would give me a weekly problem. I remember spending 8 hours daily from Monday to Friday and barely having time to deliver it in time. I found the problems and my code on my email and uploaded it to my github.There are 15 projects, ranging from quantum mechanics to fractal chaos. Some have cool graphics, like this Laplace Equation for a square wire (with visual bugs that I did not have time to fix)

I also learned the basics of Python, although I did not understand the fuss around it. Got used to FORTRAN and had no reason to use anything different. Then I graduated and reencountered the Web Development and Javascript…